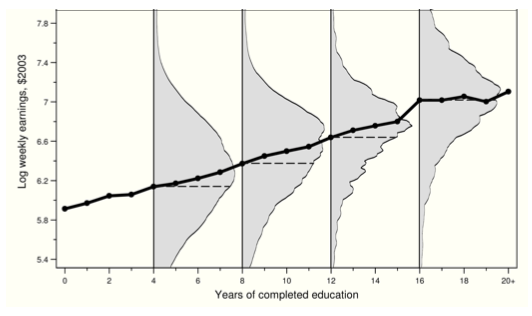

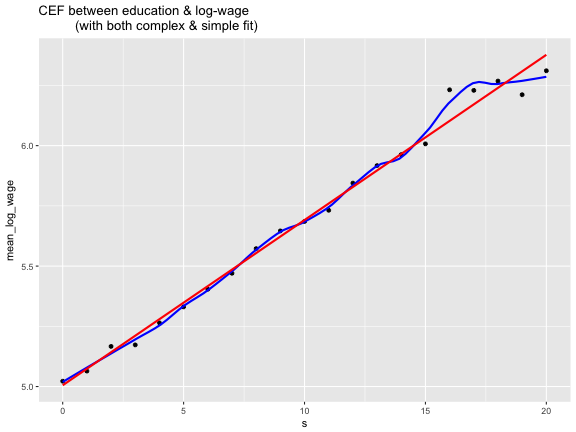

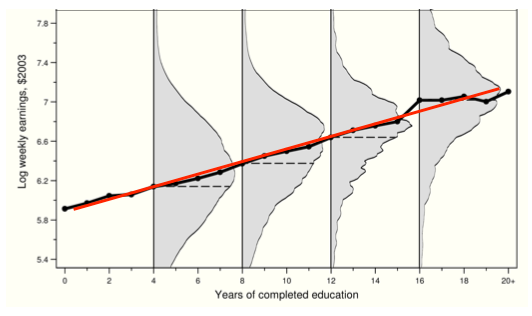

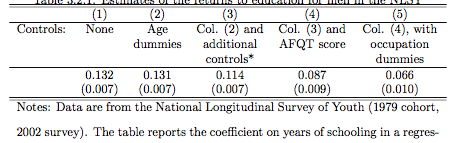

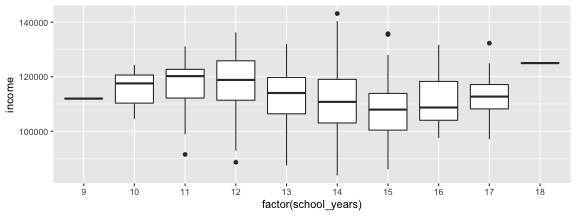

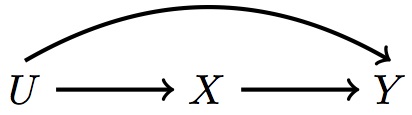

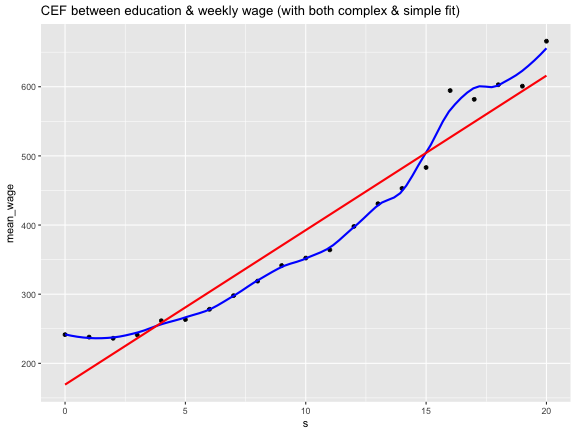

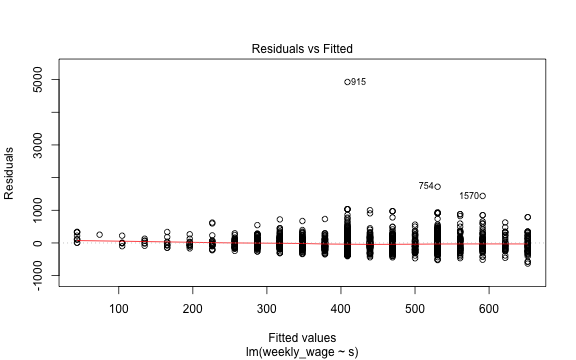

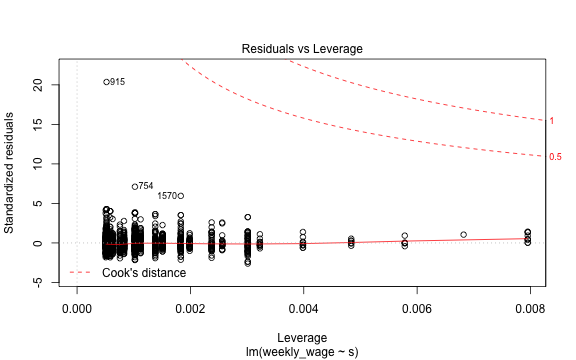

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Linear Regression is the Workhorse for Causal Inference ## ITAM Short Workshop ### Zhe Zhang, Mathew Kiang, Monica Alexander ### March 15, 2017 --- # Statistical Tools of Causal Inference Intro ### linear regression (with causal interpretation) ### causal biases / "mis-identification" in regression ### linear regression is not a restrictive methodology ??? We're going to cover these three topics. First, Matt introduced the importance of casual identification and causal questions. He also emphasized the Rubin Causal Model (potential outcomes framework). We'll return to this throughout the next few lectures. In this lecture, we talk about the basic statistical tools we use to identify causal estimates. Specifically in much of the literature, it is linear regression. In ML and data science, usually we like linear regression for a first attempt, but it's not really a "hot" model to use in general. This is because it usually is not the best predictor. However, in this case, the best prediction is not what we care about. Instead, we want to be able to identify a causal estimate. And an unbiased causal estimate. Linear regression is interpretable. We would like better prediction, but that's usually not the first priority. Let's take this next image as an example. --- # Statistical Basics - `\(Y\)` = Outcome of Interest - `\(T\)` = Treatment `$$Y = f(T)?$$` -- `$$Y = E[Y|T=t] + \epsilon = CEF + \epsilon$$` *First, we discuss the CEF; second, when is the CEF causal?* ??? The CEF is a prediction concept. First we'll discuss the prediction properties. Then, we'll discuss when we can interpret the CEF to be causal. --- # CEF for Predicting Job Earnings  - What about all the extra noise in wages? -- - What does the above line mean to us? Interpretation? .footnote[Mostly Harmless Econometrics] ??? In this example, we have years of education on the x-axis and wage earnings on the y-axis. The grey areas represent the distribution of data from each person with that wage. We're clearly not going to try to explain such a variable thing. Instead, we're looking at the systematic pattern between education and wages. --- # Recreate Graphic Data: <https://www.dropbox.com/s/gkpyivx06n9etda/ak_91_iv_qob.rds?dl=0> ```r library(tidyverse) df <- readRDS('../datasets/ak_91_iv_qob.rds') # aggregate data year_df <- df %>% group_by(s) %>% summarise(mean_log_wage = mean(log_wage)) # create CEF plot g_CEF <- ggplot(year_df, aes(x = s, y = mean_log_wage)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(span = 0.35, se = F, color = 'blue', method = 'loess') + geom_smooth(method = 'lm', se = F, color = 'red') + ggtitle("CEF between education & log-wage (with both complex & simple fit)") ``` .footnote[Data provided by Mastering Metrics] --- class: center # Recreate Graphic ```r print(g_CEF) ``` <!-- --> --- # Linear Regression Estimates a *Linear* CEF CEF with no functional form assumption: `\(Y = E[Y|T,X] + \epsilon\)` ### main assumption: assume `\(E[Y|T,X]\)` is **linear** (and additive) Using data, we then estimate: `$$\hat{Y_i} = \hat{E}[Y|T,X] + \hat{\epsilon} = [\hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\gamma} T_i] + \hat{\epsilon_i}$$` -- Or with additional covariates: `$$\hat{Y_i} = [\hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\gamma} T_i + \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} \mathbf{X_i}] + \hat{\epsilon_i}$$` Best linear mean-squared error predictor *Note: linear form is not that restrictive* *Note: not the only interpretation (weighted regression is an alternative)* ??? This is the best MSE predictor, no matter. What we need to do is to find a functional form of the explained part. By definition, Epsilon is uncorrelated and mean-zero. - In the usual linear regression, we only interpret the beta coefficients as helping to use X to explain variation in Y. Now, we'll include a causal effect of interest, gamma, and make sure that we're estimating gamma correctly. This will be the crux of what we're focusing on in this class. - Going to spend a lot of time thinking about `\(\gamma\)` and `\(\epsilon_i\)`. - Though we will just use regression, this does not limit our scope much: not limited to simple linear possibilities (interactions, feature transformation, semi-parametric methods) --- # Causal CEF = Causal Linear Regression So far, this is prediction, and fits for all linear regression. When can we argue that the `\(\hat{\gamma}\)`, (or CEF) is *causal*? -- Ask: *does the treatment variable, `\(T_i\)`, in the linear CEF, have (conditional) independence from the potential outcomes? i.e., can we consider the treatment to be random* -- Consider observations `\(Y_i, T_i\)` where `\(T_i\)` is a binary treatment. `$$\left\{ Y_{0i} \equiv Y_i|_{T_i=0}, \quad Y_{1i} \equiv Y_i|_{T_i=1} \right\}$$` `$$Y_{ i,observed } = Y_{0i} + (Y_{1i}-Y_{0i})T_i$$` Simple linear regression: `\(Y_i \sim \gamma T_i + \epsilon_i\)` - `\(avgObservedEffect = \hat{\gamma} = E[Y_i|T_i=1] - E[Y|T_i=0]\)` --- # Causal CEF = Causal Linear Regression `\(avgObservedEffect = \hat{\gamma} = E[Y_i|T_i=1] - E[Y_i|T_i=0]\)` Is this causal? -- Use the potential outcomes formula `\(Y_{ i,observed } = Y_{0i} + (Y_{1i}-Y_{0i})T_i\)` and expand the observed effect. `$$\begin{eqnarray*} avgObservedEffect=\hat{\gamma} & = & E[Y_{i}|T_{i}=1]-E[Y_{i}|T_{i}=0]\\ & = & E[Y_{0i}+(Y_{1i}-Y_{0i})T_{i}|T_{i}=1]\\ & & -E[Y_{0i}+(Y_{1i}-Y_{0i})T_{i}|T_{i}=0]\\ & = & E[Y_{0i}|T_{i}=1]+E[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}|T_{i}=1]\\ & & -E[Y_{0i}|T_{i}=0]\\ & = & E[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}|T_{i}=1]+\left\{ \underbrace{E[Y_{0i}|T_{i}=1]-E[Y_{0i}|T_{i}=0]}_{possible\_bias}\right\} \end{eqnarray*}$$` How do we ensure the second term is zero? `$$CIA \equiv \left\{ Y_{0i}, Y_{1i} \right\} \bot T_i$$` ??? Independence of Y_0i is obvious why it's an issue. Indepdence of Y_1i is less mathematically clear, but perhaps only those who benefit will accept treatment. --- # Conditional Independence Assumption (CIA) *Most work will be spent convincing others that treatment outcomes are uncorrelated with the counterfactual / potential outcomes* Previous example works for an RCT, with binary treatment. - comes with built-in conditional independence assumption (CIA) -- In observation data, we usually need to manipulate data to get CIA - "conditional on other covariates, `\(\mathbf{X_i}\)`, we get CIA" `$$\left\{ Y_{0i}, Y_{1i} \right\} \neg\bot T_i; \qquad \left\{ Y_{0i}, Y_{1i} \right\} \bot T_i|\mathbf{X_i}$$` ??? Obvious to avoid that good people go to good schools. Also, avoid that people who are bad go to good schools. --- # CIA & Linearity If our CIA is: `\(\left\{ Y_{0i}, Y_{1i} \right\} \bot T_i|\mathbf{X_i}\)` *e.g. conditioning on neighborhood wealth, whether you go to a 'good' school or a 'bad' school is independent of your counterfactuals* Do we need to estimate a causal effect for each possible value of `\(\mathbf{X_i}\)`? -- Linearity assumption of the CEF makes things simpler: *binary treatment has additive effect, independent of other covariates*. -- The assumed linear model `$$\hat{Y_i} = [\hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\gamma} T_i + \hat{\mathbf{\beta}} \mathbf{X_i}] + \hat{\epsilon_i}$$` `$$avgEffect = E[Y_i|T_i=1,X_i] - E[Y_i|T_i=0,X_i] = \gamma (1 - 0) + (\beta X_i - \beta X_i)$$` --- # What about non-binary treatments? Consider the treatment effect of different years of schooling.  Linearity assumption again simplifies things: *each year of schooling has a constant, additive effect.* `$$CIA \equiv \left\{ Y_{t_1,i}, Y_{t_2,i} \right\} \bot t|\mathbf{X_i} \quad \forall t$$` .footnote[Mostly Harmless Econometrics] --- # What about non-binary treatments? The estimation of a treatment effect is simple in a linear form: `$$E[Y_i|T=T_a,X_i] - E[Y_i|T=T_b,X_i] = \gamma (T_a - T_b) + (\beta X_i - \beta X_i)$$` (a) We can focus on the overall average treatment effect. (b) simple, robust interpretation: assumes that `\(E[Y|T]\)` is linear. - In the linear regression, `\(\mathbf{X_i}\)` controls for the other variation - In other notation, the linear assumption easily gives us: `$$\hat{\gamma} = \frac{\partial{Y}}{\partial{T}}|_{X_i} = \frac{\partial{Y}}{\partial{T}}|_{\forall i}$$` ??? Important to be cognizant that this is what you're estimating however. --- # Causal Regression Discussion (almost) All data is observational. If you think you have an experiment, it's probably still observational data. -- - what can we do: "estimating systematic randomness" - we know we can't explain (close to) everything - instead, we want *unbiased* estimates of particular causal patterns - how does the distribution of `\(Y_i\)` change *wrt* `\(T_i\)`? - (best) linear approximation to the true CEF, with **interpretable** coefficients - the **average** treatment effect - (anecdotally robust) -- - important to argue robustly for conditional independence assumption (CIA) - we rarely "prove" causality - we argue using domain expertise and theory that we are not facing biases - a good analysis shows several versions of results/models, to ensure the results are "robust" to possible biases and assumptions - control variables are important, but not always convincing ??? We know that it's not that simple to explain complex real-world outcomes with a linear model. We need to argue using using theory that our estimate of the CEF is okay. However, if we believe we have an unbiased estimate, this is useful approximation. The exact numbers usually aren't that crucial. And linear models are fairly robust. Even if truly non-linear, there is value in having a robust linear approximation. --- # Note on Using Causal Terminology ### Causal {"effect", "leads to", "results in", "because of", "impact"} ### Observed Patterns {"related with", "pattern", "correlation", "tends to move with", "observed"} ## Note on Data ### be careful where your data comes from!! --- # Attacks on the CIA assumption - omitted variable bias, selection bias - regression functional form <br/> - external validity - measurement noise/error - reverse causality, simultaneous causality --- # Omitted Variable Bias: concerns in `\(\epsilon\)` term Related to, but not necessarily *self-selection bias* Consider a treatment bringing people from `\(T_b\)` to `\(T_a\)`. `$$Reg_{TRUE} \equiv Y = \gamma T_i + \beta \mathbf{X_i} + \delta Location_i + \nu_i$$` -- But we ignore location effects. `$$Reg_{estimate} \equiv Y_i = \gamma T_i + \beta \mathbf{X_i} + \epsilon_i$$` What if `\(Location\)` is correlated with `\(X_i\)`? What if `\(Location\)` is correlated with `\(T_i\)`? What is `\(E[\epsilon_i|T_i]\)`? What is `\(E[\hat{\epsilon}_i|T_i]\)`? --- # Omitted Variable Bias: concerns in `\(\epsilon\)` term We omitted location in our estimation, so `\(E[\epsilon_i] = \delta Location_i + \nu_i\)`. -- Correlation is what hurts us: `$$E[\epsilon_{i,true}] = 0 \\ E[\epsilon_{i,true}|T_i,X_i] \ne 0$$` In other words, `$$\epsilon_{i} \not\bot T_i$$` --- # Omitted Variable Bias: Results in biased estimates Consider a treatment bringing people from `\(T_b\)` to `\(T_a\)`. `$$\begin{eqnarray*}avgObservedEffect & = & E[Y_{i}|T=T_{a},X_{i}]-E[Y_{i}|T=T_{b},X_{i}]\\ & = & \gamma(T_{a}-T_{b})+\beta X_{i}-\beta X_{i}\\ & & +E[\epsilon_{i}|T_{a}]-E[\epsilon_{i}|T_{b}] \end{eqnarray*}$$` If `\(E[\epsilon_i|T_a] >> E[\epsilon_i|T_b]\)`: - Omitted variable bias is "hidden" inside `\(\epsilon_i\)` between those treated and untreated. `$$E[Y_i|T=T_a] - E[Y_i|T=T_b] = (\gamma + Bias_{OVB})(T_a - T_b)$$` `\(E[\epsilon_i|T_i=T_a]\)` could be **positive** if wealthy locations have peer effects both for future earnings and on encouraging extra treatment. `\(E[\epsilon_i|T_i=T_b]\)` could be **negative** if low-income locations have nearby crime and travel time that reduces both future earnings and treatment. *if there were location effects, uncorrelated with treatment, we could still estimate treatment effects* --- # OVB Example: Estimated relationship between schooling and wages:  .footnote[Mostly Harmless Econometrics] --- # OVB Synthetic Example ```r library(tidyverse); nobs = 500 df_educ <- data_frame(iq = runif(nobs, min = 1, max = 100), school_years = round(16 - 0.05*iq + rnorm(nobs)), income = 20000 + 5000*school_years + 5000*rnorm(nobs) + 500*iq) ggplot(df_educ, aes(x = factor(school_years), y = income)) + geom_boxplot() ``` <!-- --> --- # OVB Synthetic Example: Misspecified Model ```r summary(lm(income ~ school_years, data = df_educ)) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = income ~ school_years, data = df_educ) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -28236 -7367 -30 6959 31113 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 132671.1 3465.7 38.282 < 2e-16 *** ## school_years -1473.4 255.9 -5.758 1.49e-08 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 10250 on 498 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.06241, Adjusted R-squared: 0.06053 ## F-statistic: 33.15 on 1 and 498 DF, p-value: 1.494e-08 ``` --- # OVB Synthetic Example: Unbiased Model ```r summary(lm(income ~ school_years + iq, data = df_educ)) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = income ~ school_years + iq, data = df_educ) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -14691.4 -3337.3 82.2 3448.3 18262.2 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 15509.5 3463.9 4.477 9.38e-06 *** ## school_years 5257.5 214.4 24.518 < 2e-16 *** ## iq 522.4 13.4 38.983 < 2e-16 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 5093 on 497 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.7689, Adjusted R-squared: 0.768 ## F-statistic: 826.9 on 2 and 497 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16 ``` --- # OVB Illustrated Recall our earlier discussion of confounders:  --- # OVB Thought Examples what might be omitted in observational data? - effect of air quality policy - effect of advertising campaign - effect of customer loyalty campaign - adoption of a mobile app - calling customer service - effect of changing a search algorithm -- when might controlling for covariates be OK? - when job training is randomized depending on skills - when comparing similar groups, with different treatments - when studying random levels of advertising exposure, conditional on user online behaviors and history --- # Selection Bias + External Validity Selection bias falls into two camps: 1. self-selection into treatment (schooling, job training, email campaign) -- 2. sometimes we're OK with this though, it can sometimes estimate the "treatment effect on the treated" - still need to worry about other omitted variables, like the timing of adoption - external vs internal validity - "average" causal effect - depends on the goal of the causal analysis --- # Regression Functional Form Bias - what if the CEF is non-linear? - e.g. wages is usually not a linear relationship in covariates - **transform**: we usually use `\(\log (wage)\)` instead! - `\(\log(wage) \sim \beta_0 + \gamma Educ_i + \epsilon\)`; interpret `\(\gamma\)` as a percent increase in wage per school year! --- # Example: Regression Functional Form Return to schooling and future earnings example. ```r df <- readRDS('../datasets/ak_91_iv_qob.rds') year_df <- df %>% group_by(s) %>% # use nominal wage here, instead of log_wage before summarise(mean_wage = mean(weekly_wage)) g_CEF <- ggplot(year_df, aes(x = s, y = mean_wage)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(span = 0.35, se = F, color = 'blue', method = 'loess') + geom_smooth(method = 'lm', se = F, color = 'red') + ggtitle("CEF between education & weekly wage (with both complex & simple fit)") ``` .footnote[Data provided by Mastering Metrics] --- class: center # Example: Regression Functional Form ```r g_CEF ``` <!-- --> --- # Example: Regression Functional Form *Like any regression, important to check estimation diagnostics.* ```r set.seed(10) bad_fit_lm <- lm(weekly_wage ~ s, data = sample_n(df, size = 2000)) plot(bad_fit_lm, which = 1) ``` <!-- --> --- # Example: Regression Functional Form *Like any regression, important to check estimation diagnostics.* ```r plot(bad_fit_lm, which = 5) ``` <!-- --> --- # Regression Functional Form Bias - what if the CEF is non-linear? -- - other types of non-continuous outcomes? - 0/1 outcome variable (logistic regression, Probit regression has a more economic interpretation) - Poisson or negative-binomial regression for counts - sometimes our features are non-linear too `\(\beta_i age + \beta_j age^2\)` - or interactions can be important too, e.g., occupation/test scores interactions - Truncated/censored observed outcomes (e.g., test scores, wage) - Tobit regression, assumes a latent variable that can take negative values) - Attrition bias - flexible semi-parametric methods: `\(Y_i = \beta_0 + \gamma T_i + f(\mathbf{X_i}) + \epsilon_i\)` *Note: important to think critically about where the (potential) data comes from* *Note: almost all interesting data comes from human decisions* --- # Despite Caution, Causal Work Still Useful - Raj Chetty et al., policy impact - Work on piracy affecting movie studios - Health insurance studies - Air quality impact studies - Studying optimal advertising policies --- # Reference Sources - Mostly Harmless Econometrics - Osea Giuntella, slides